Alex has a year-long project for the gifted program at school. It’s a wide-open project where each of the kids in the class can basically choose to do whatever they want, as long as it requires a bit of brainpower. I think the real goal is not necessarily the project itself, but the process of defining a project, planning it, finding “advisors” to help, meeting deadlines, and writing reports. Overall it’s pretty cool, and I hope it’s a good learning experience.

Anyway.

A few months ago Alex was asking me for ideas about what to do. We brainstormed a few things, and finally I asked him what his interests are. What sorts of things does he enjoy that could conceivably be combined into a year-long project? He replied “video games, computers, and Lego”. After a bit more thought, we came up with a good idea: he could write a computer game.

His computer experience to date consists of writing a Zork-like text game in Chipmunk BASIC (yes, it’s really called Chipmunk BASIC). It was a “choose your own adventure” game where you were given a description of where you were, and you had to select which direction to go. The goal was to find the submarine and leave the island. Or something like that.

All in all, it wasn’t bad. At its heart, it was really just a series of if-then-else constructs, but the logic had to be self-consistent so you could– for example– go north and then south and end up where you started. He did a good job, and there were maybe eight or ten different “rooms” in the game. Many of them killed your character, oddly enough.

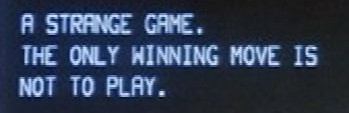

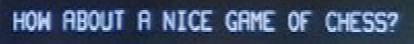

He really enjoyed that project and was excited about the prospect of writing a game that was slightly more advanced. More to the point, we decided he would write a computer opponent (a so-called “AI” player) so it was a more interesting game. We talked about Tic Tac Toe but anyone who’s seen Wargames knows that’s a silly exercise because if you start in the center, you can always force a draw.

The next obvious option was…

But chess is actually quite complex, with an enormous number of possible moves at any point in the game (I did a science project about it back in junior high). So we ruled that out. However, checkers struck our fancy because it’s much simpler but still confined to a small game board and has a much more limited number of moves and countermoves.

Alex suggested Connect Four, and after some discussion we decided that would be even better. The move options are even more limited than checkers: instead of fifteen pieces with two possible (diagonal) moves– four if they’re kings– we have seven vertical slots with only one move each. The interface would be drop-dead simple: the game would prompt the user to enter a slot (one through seven) and would drop a checker in that slot.

We’ve decided to write the game in Python. It’s a powerful but not-too-difficult scripting language, highly recommended as a good learning language. There are a gazillion libraries for it, including graphics packages that might be nice for dressing up the game once we get the basic logic worked out. I know a (very) little bit about Python, having written a couple of database routines in it, so it will be a bit of a learning process for both of us.

This week, during Thanksgiving break, Alex is going to work on learning very simple Python tasks so he can grasp the syntax and grammar. Then we’re going to really lay out the program architecture, identifying modules like user input, graphic display, error checking, win/loss conditions, and the most complicated piece of all: the AI.

This won’t be true artificial intelligence, of course, but it should be interesting to write an algorithm that decides how to move. Time permitting we’ll change the console interface to graphics and maybe even animate the pieces dropping into their slots.

The next step would be Connect Four Million, an awesome but long-lasting game which can only be played by immortal brothers with nothing better to do.

(Disclaimer: if you haven’t seen Lost, you won’t get this joke.)